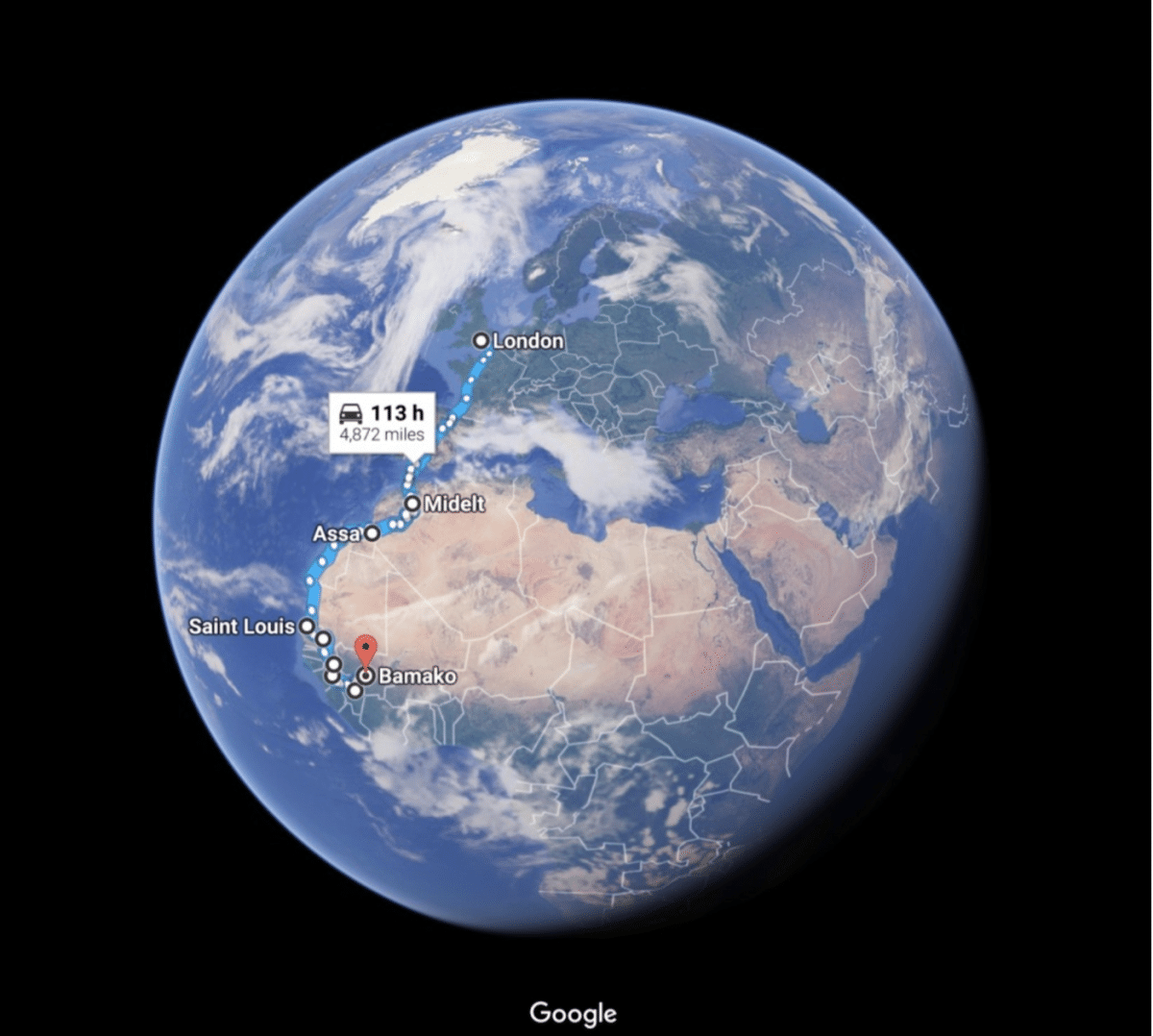

A five thousand mile commute overland from London to Mali by Marcus F Stevens

I’ve always regarded blogs as harbouring the sort of self-indulgent small talk which bores us all; inane, desultory, mini-updates neither telling a story nor addressing a point. An incoherent musing of one’s day-to-day life written by those who seem to have overlooked the stories that readers might actually want to hear. So, it came as a surprise when I found myself thinking about writing one for this trip. I hope, in fact, that it’ll end up less a blog and more a series of articles, each with more photographs than prose. I will endeavour to produce something complete, interesting, and hopefully mildly inspiring — country by country — apologies in advance if, or when, I fail.

Nine months before my Dad and I pulled off the drive and headed for Mali, I bought a twenty-five year old short wheelbase 70 Series Toyota Land Cruiser from a dubious family run dealership in Burton-on-Trent. Soon afterwards I had an idea. I was in the early stages of applying for a job in southern Mali, working for a British gold mining company providing healthcare for their workers and assisting in their community development efforts. If all went to plan, I thought, I’d drive down there. A commute, an adventure and a challenge beyond anything I’d ever done before. I’ve always thought that the best ideas are seeded from ridiculous, irrational and possibly arrogant delusions about what one is capable of. Soon, however, the idea began to dominate my thoughts and all the positives and possibilities began to crystallise through the fog of warnings, perils and risks. I had to do it.

The first hurdle was deciding whether it was actually feasible, were any of the countries on the west coast route — Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal and Guinea — in the midst of civil wars, overrun by terrorists or controlled by warlords? The UK travel advisory website suggested that there was a ‘high threat from terrorism in Morocco’, they advised against ‘all but essential’ travel to Mauritania, in Senegal ‘attacks could be indiscriminate’, and while Guinea was now Ebola free there were ‘ongoing political tensions’. Choosing to ignore all of this I sought advice from anyone who had recently been on the ground and emailed a company running overlanding tours between Morocco and Senegal. They explained that they didn’t spend much time in Western Sahara, a disputed territory south of Morocco currently controlled by the Moroccans, or head too far east in Mauritania but otherwise the route was fine. I figured that even if they were trying to rope in more business you couldn’t run a company doing such trips if people were regularly being kidnapped.

With that email I had the rough assurance I needed. I wasn’t being completely ridiculous and I began floating the idea to various friends. I didn’t want to do it alone and so would need someone to accompany me. Most people thought the idea was crazy or that I had a death wish, one close friend just said “it sounds a little silly to me”. A small minority shared my enthusiasm, resenting that they couldn’t get the time off work and a couple more insisted I keep a blog so they could stay up to date. That gave me an idea, there must be other people doing this and keeping blogs of their trips, maybe they would contain the up-to-date information I needed. Thankfully, there were loads and most were wonderfully dull and heavy with details of vehicle preparation, packing lists and border nightmares. I obsessively gathered as much information as possible. They also offered the perfect get out when someone claimed that I would ‘definitely’ be killed en route. If Cat and Charles, an Oxford based couple in a Land Rover Discovery, could avoid being dressed up in orange jump suits and beheaded then I damn well could too.

The blogs also provided the first insight into the two different types of off-roading psyches; those with all the gear who seemed to avoid using it and those whose old, beat-up trucks were always on the road and never in the garage. For a bit of inspiration I headed to the Adventure Overland Show, and met both.

Benjy was there with the 80 Series Land Cruiser he’d driven twice around Australia and then imported to the UK when he returned. A member of the 300,000 mile club it was still going strong though lacking a little power, in his opinion. “I’ve got a spare lorry engine on the farm that I’m going to put in next week”. Despite having been born in rural Wiltshire he padded round in a filthy pair of UGG boots and a wife beater and looked like the sort of guy who could repair a badly mauled radiator thousands of miles from anyone in the middle of the outback.

In contrast, close by I spoke with a chap who talked me through the solar panel, inverter and extra batteries he’d recently installed in his shiny blue Hilux. “Enough power to run my fridge and all my lights for a week”, he beamed. Must have a big trip planned I thought. “We camped in a field in Wales last week”, he said, gesturing to his girlfriend who looked like she had heard the battery story far too many times already.

Armed with all the blog and Youtube-sourced information I needed I had come up with a list of the things that I would need to buy, repair or modify in order to successfully drive 5000 miles. The seats were reupholstered (after twenty fives years they had essentially no padding and became rather uncomfortable after more than fifteen minutes driving) by a small family run business near Yeovil whose yard was filled with beautiful old sports cars having new leather interiors fitted. I stripped out the rear seats and fitted a wooden bulkhead and the beginnings of a storage system. I bought a winch and an LED light bar, a portable fridge and an auxiliary battery pack that would run off the cigarette lighter power output. My brother spent a weekend driving around Scotland buying second hand items I’d found on Gumtree, an almost brand new Eezi-Awn roof tent and five BFG mud-terrain tyres.

The tyres came from someone who had been building up a Defender for an overland trip to Cape Town when his wife was diagnosed with cancer. I can imagine they’d spent years dreaming of the trip but put it off until retirement, and now the chance was gone. I thought of some of the friends I spoken to who’d said how much they would love to do a similar trip but that work was too busy or that they needed to save up for their wedding or a new car. Maybe they’d find the time once they got that promotion or after they got married, maybe….

The more I prepared, the more I realised I didn’t know, at times planning merely felt like compiling a list of unanswerable questions. While it was unnerving I soon realised this was what I had always been looking for, an adventure to places that hadn’t yet been penetrated by technology’s omnipotent gaze. There were no list of best restaurants, no Google Street View and no public transport timetables only a click away.

A little research prior to most trips will tell you everything you need to know — how to get there, when to go, and how to travel — revealing all the secrets you could have stumbled upon yourself. Thousands of photos, reviews and videos seek to inform our opinions before we’ve even got on a plane. Visiting a place in person merely feels an act of confirmation, double-checking that everything you have read does indeed ring true. In contrast, west Africa simply hasn’t been documented and so one is forced to travel with no expectations, unsure what lies around every rutted, dusty corner. This journey I hoped would offer an experience far more expansive and multi-dimensional than the narrow scope with which most people see Africa while on safari; glamping, sunset dinners, the lone lion surrounded by open topped trucks and peering tourists snapping away.

As preparations continued I still had one major problem, I didn’t have anyone to accompany me. My best hope was Nick, a yes man and one of my oldest friends who seemed keen and said he’d find out how much time he could get off work. Around the same time, I was trying to convince my parents that the whole idea was vaguely sensible, I knew what I was doing and that the co-pilot situation would be resolved shortly. I sent them a link to a drone-shot video (https://vimeo.com/161625738) of a group of 4x4s in the Moroccan desert. It looked awesome, how could anyone not want to join me.

The next day I got a text from my dad. “Tell Nick to piss off, I’m going to come.” My mum has since claimed that she orchestrated the plan, subtlety suggested that dad accompany me, “to keep him safe”. Secretly she knew that we’d have a brilliant time together and that not many others could put up with me for five weeks.

In early August I finished working in Yeovil, drove home after a final paediatric night on-call to argue with the landlord about how much of the deposit we’d get back and then packed up the Land Cruiser and drove back to my family home. With the Mali job still not confirmed I enjoyed a week in Morzine cycling with a close friend and then a month at home of glorious unemployment. At last the call came that the job was mine (pun intended) which prompted a mild panic, what for so long had seemed foreign, distant and exciting now became very real and mildly terrifying. In the week before I flew I had a night in London with friends, a Lyme disease scare and a few vaccinations.

Flying down to Bamako I looked at the flight map and the smooth arcing route and pondered when the best time to do the drive would be. Dad and I hadn’t yet decided on when exactly we should do it; after this rotation, early in the new year or even next summer? Shortly after I arrived on site we decided on departing in February the following year, giving ourselves a full six weeks to make up the miles whilst also avoiding the wet season.

After ten weeks and an education in the world of gold mining I flew home for 36 hours before heading back to Heathrow for two weeks in Australia. Brisbane’s customs officials didn’t take too kindly to my recent travel and it was nearly an hour before I could convince them I wasn’t in cahoots with Mali’s Islamic terrorists. It didn’t help that my phone, which they demanded to see, had decided to mix up (it was new) the order of my photos and put the ones from Oman and Jordan first. “Why have you spent so much time in the Middle East?” Neither seemed to understand the idea of winter sun.

After two weeks of battling Australia’s awful drivers, drooling over 4x4s, trying to surf and catching up with friends I flew home for a Christmas week with family. Dad and I made some progress on the truck, the tyres my brother had bought in Scotland were fitted on new steel rims and then everyone had to help fit the roof tent, all 80kg of it. I headed back to Mali in time for New Years Eve, celebrated with sweeping sunset views looking over into Guinea. If all went to plan, I thought, I’d be rolling into camp in three months time from over that horizon, I couldn’t wait.

During the next six weeks on site I spent all my spare time trying to make sure we’d be ready to leave soon after I returned home. I worked how and where to get visas, what documents and insurance we’d need, and what else we needed to buy. The boxes began to stack up in my room back home; toolkit, oil, air compressor, new suspension and maps for each country. I’m sure the postman thought I was running some kind of Silk Road drugs ring. Weekly FaceTimes with my dad become slightly fraught, it appeared very little progress was being made at home leaving us with a lot to do in the six days we’d have together once I got back. Dad claimed a variety of excuses, I suspected drinking coffee on the sofa with the dog was getting in the way of finishing the rear storage unit or working out where the fridge was going to live. Luckily my colleagues on site were a wealth of information and filled in any gaps. Having worked in west Africa for years they had contacts in every country we passed through.

Those six days at home were worse than envisaged, there was a lot to finish in the truck to make sure everything fitted and could be secured, decapitation in the event of a crash or rollover had to be avoided so everything had to be tied down. We spent a morning in London getting our Guinean visas, went food shopping, tested all the equipment and fitted the awning, a last minute purchase to protect us from rain or sun if we stayed in one place for a day.

Very rarely do I get nervous or apprehensive before a trip. However, it was inescapable in the days before leaving. A nagging feeling that we’d missed or overlooked something, we’d fall into a bureaucratic hole we couldn’t get out of, the truck would blow up in a puff of smoke miles from anywhere, or a myriad of other unpleasant scenarios ran through my mind.

On Sunday afternoon, a week after I had got back we loaded the last bits, made sure we had our passports, said our goodbyes and hit the road. As we trundled down the M20 I wondered what others saw as they overtook us; just a slow, old, packed-to-the-brim 4×4 helping someone move house or someone with five weeks of adventure ahead of them. It occurred to me that no one on this motorway was likely going anywhere as exciting as us, filling me with a sense of pride.

Having planned the trip, tentatively for a year, realistically for months, and obsessively for the last weeks, it felt good to be en route. I hoped we’d discover that for all it’s perils, Africa offers one of the last great blank canvases to explore.

Our first night we found a quiet place to camp alongside a canal an hour north east of Pairs. We finished off our packed lunches, setup the tent and settled in for our first night on the road. The following morning we battled Parisian traffic on our way to the Malian embassy to get my Dad’s visa. Sitting and eating pastries we waited for the fixer to call with the good news. By mid-afternoon we had the documents in hand and were on our way.

By the end of day three we’d reached the pyrenees, confirmed that no French campsites are open in February and realised we hadn’t really prepared for European temperatures. Pulling off the main valley road in the dark we took a small winding road heading up to the Col de Marie-Blanque and found somewhere to camp for the night.

In the morning the truck complained as we crawled up and over the col. For the first time on the trip the scenery forced regular photo stops as we wound down into the valley. After crossing into Spain we stopped and set up the drone for it’s first flight. I had spent months considering which model to buy. The cheapest DJI models start at about £400 with the priciest costing many thousands. I eventually realised that I’d probably crash it at some point and would rather watch £400 worth of camera and propellor falling out of the sky than over a thousand! I put the drone up, got in the passenger seat and it chased us down the road, filming the scene from 100ft up. Unfortunately, however, during my two previous ‘training’ flights in the local park back home I hadn’t realised that it had a maximum flight distance. Having reached 1600ft from it’s take off point it would refuse to go any further. With it’s 22 minute battery life diminishing fast we had to find somewhere to turn on the narrow mountain road and head back up to rescue it.

On day four we managed 360 miles in nine hours. By this point we had realised that the truck wasn’t designed to make up ground quickly. Built with 90 bhp and a gearbox designed for neither tarmac nor motorways meant that 55 mph was our maximum. Knowing this we rarely followed main roads or motorways and instead stayed on the back roads, winding our way south towards the coast.

By late afternoon the next day we had reach Jimena, and the first open campsite we’d encountered, Camping Los Alcornocales. We were greeted by a band of locals, clearly deep into an afternoon boozing session, who stumbled out of the campsite bar to assist us in any way they thought might be useful. Thankfully, the lure of more beer eventually proved too much and we escaped to set up the tent and shower. Deciding we’d rather not be the centre of anymore drunken attention we strolled into Jimena.

Set on a precipitously steep hillside and with postcard worthy winding streets we set out to find dinner and a beer. We ended up bar crawling the main street in order to find somewhere decent; the first two offerings didn’t serve food and the third contained a British family of hippy Devon ancestry who thought it appropriate to loudly and rudely discipline their children for merely playing with the family dog. The fourth choice was staffed by a hobbling, bow-legged grandfatherly Spanish man who took our order and showed us to a table in the covered sun terrace at the back of the bar. As we sat down a late middle aged woman sipping white wine smiled welcomingly and said, in a soft Irish accent, ”evening, are you here for the quiz?” We had stumbled into the weekly expat pub quiz, clearly an important event as the room quickly filled and more tables had to be dragged in. With a long-standing hatred of bar quizzes, stemming I think from those at Oxford designed to humiliate and expose gaps in one’s general knowledge, I suggested we retreat to the main bar area to enjoy dinner.

The following morning we headed for the port at Algeciras, bought our ticket and lined up behind cars piled high with anything that Europe had to spare. We got chatting to a group of kayakers heading to Marrakech and the High Atlas to catch the snowmelt. A multinational group, some were professionals kayakers in Europe while other led rafting trips in the US.

Having boarded the ferry and waited in line to get my passport stamp I watched as an elderly Japanese couple politely asked two of the kayakers for a photo. They happily obliged. Soon, however, two wasn’t enough and one by one the photo burgeoned with additional kayakers and geriatric Japanese tourists. Clearly they were more famous than I had guessed.

We exchanged numbers and promised to send them pictures of any rivers we saw alongside details of the altitude so they could decipher how fast the snow was melting and where to head next. Dad, however, saw through the snowmelt chat and once back in the car and waiting to disembark delivered his grand theory. One of them a CIA agent deep undercover in the kayaking scene and was collecting intelligence on Morocco. Those of you who know my father can make a judgement about how likely this is to be true. So not to blow his kayaking cover or expose any CIA tactics I won’t divulge his reasoning. Though I will say, he did have a mighty fine Team 6 beard and managed to dodge the Japanese paparazzi situation with ease.