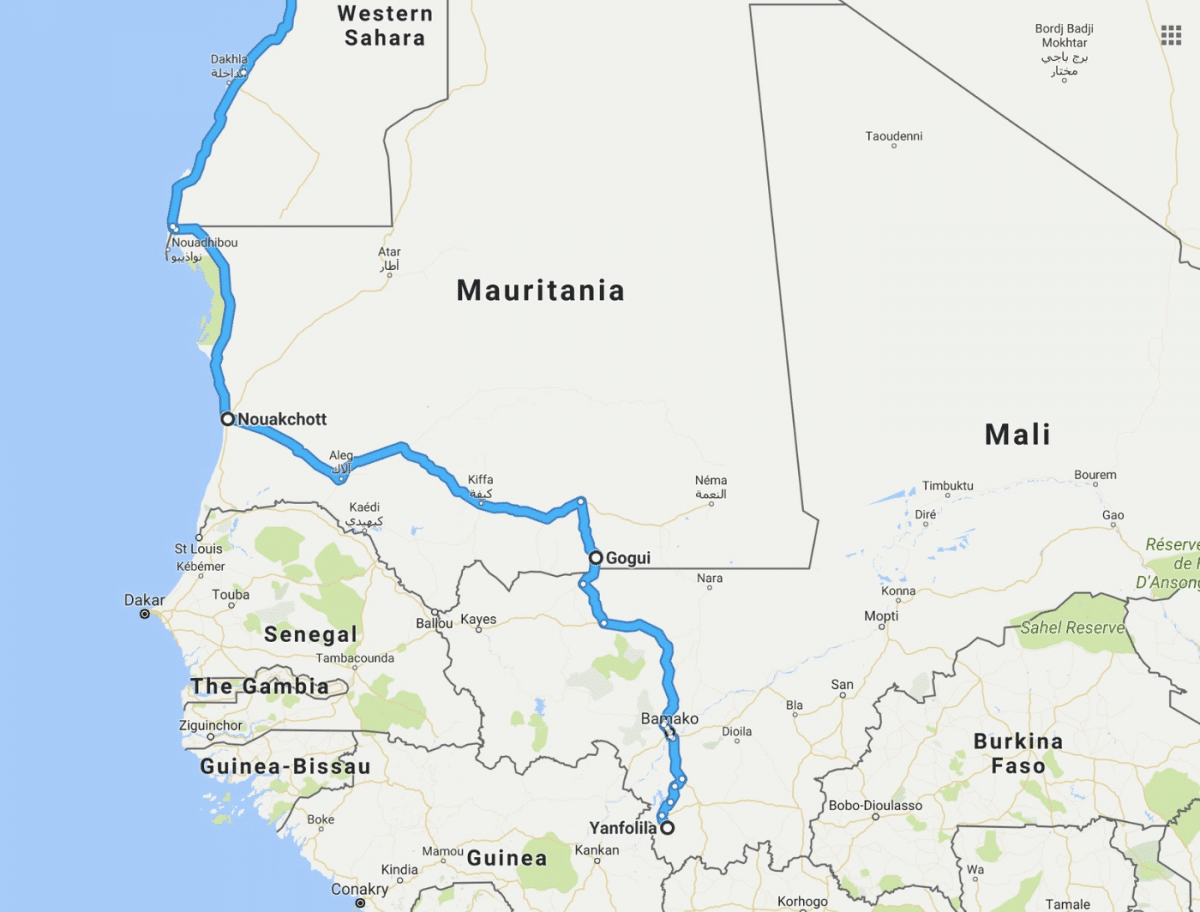

Having crossed into Mali without passing through a formal border post, our first job in country number eight was to find the nearest gendarme (police) and douane (customs) office to be officially stamped into the country. An important point, if only to avoid problems when we came to leave the country, my father in a few days and myself in a couple of months. Luckily, now we were almost at journey’s end I knew the local towns and where we would be able to sort our paperwork.

The tired and crumbling offices were sat side by side and identical except for the uniforms of the officers chatting outside. We appeared to be a rather irritating distraction and had to cajole them into doing their jobs, stamping our passports and issuing us a temporary import permit for the truck, valid for two months. Afterwards we had lunch, picked up some supplies and headed north out of Yanfolila towards Lake Sélingué, a spidery artificial lake formed when the Sélingué Dam was built in 1980s. We were in the midst of the mango harvest and everywhere we saw evidence of the gluttony; grinning children covered in juice, discarded mango pits littering the trails and everyone dragging the biggest stick they could find, prodding and poking the laden trees.

The bush was dotted with lots of small villages and we spent our time finding somewhere quiet for our last night rough camping. The following day we only had a couple of hours to go before reaching our destination, and the end of the trip. We had a shower under the solar shower’s scalding water and settled down to our last night surrounded by the African night.

Before leaving, I thought I’d look back on the places, the vistas and the landscapes, or maybe the challenges and the close calls. But, in the end, it was the people we met who took centre stage as the evening progressed. It’s seems decidedly cliche, and painfully lacking in insight, but it was genuinely unexpected. Each of them had themselves been totally unexpected and all added to the trip, however short a time we’d spent with them; Dick and Gigi, Christian, Jean, and Gerdette, to name only a few. Many we stayed in touch with during and after the trip. The world is full of extraordinary people living lives very different to our own. To share in their experience and see the world through their eyes was a privilege.

With the burner on, water boiling for our dinner and sipping on a beer, I thought of the continent’s history and those who had come before; travelling, pilfering, trading and stealing. I recalled the books I’d read as I sought to deepen my understanding, learning from those who have dedicated their lives to the African cause, unraveling the complex reasons that in some places have left millions wandering the streets with no work, money, dreams or hope of a better day.

The next morning we packed up for the last time and set off for the finish line. The Yanfolila Gold Project had been my office for the past six months, as a doctor I was responsible for looking after all the workers as they mined, processed and refined rock and earth into gold. I was almost at work, the commute almost over, and the final destination felt unworthy of the journey; familiar and friendly, the antithesis of the weeks we had spent on the road.

It was, however, a relief to have made it safely, with a healthy vehicle and time to spare. Moreover, it was brilliant to catch up with colleagues and friends. We stayed up late into the night chatting, everyone wanted to know how it had gone and where’d we’d been. Many of the South Africans I worked with had spent long periods working in Senegal and Guinea and could picture exactly the places we’d been. Having relied on their advice and guidance in the planning stages it was fantastic to be able to regale them with stories of a successful trip.

Ever since taking the job I had worked alongside a Cameroonian doctor. Soft-spoken, deeply religious and disciplined, Didier and I had become good friends and worked very closely together. I remembered a conversation months ago when I first told him what I was planning. “You are not hungry Marcus, that is why you do these things,” he said as I showed him Youtube videos of 4x4s racing though the Moroccan desert. “In Africa we are hungry.” As someone who often joked about his weight and his latest diet this was something that clearly didn’t apply to him. But still he was incredulous, why would one purposely seek adventure, misfortune and discomfort when the couch was comfy and air conditioning guaranteed a cool wafting breeze. Despite his initial bemusement, the overlanding idea clearly took root as a few months later he announced that rather than fly to Dakar later that year he was planning a road trip instead.

Now that we’d arrived, I was due to work for the next two months. Meanwhile, my dad was due back at work himself, in the U.K. After 48 hours at the mine we started on the 6 hour drive up to Bamako and a final farewell at the airport. En route my mapping app informed me were on the Trans-Sahelian highway, a slightly grandiose name for a wavy and rutted road, the consequence of tar baking under a 40 degree sun and battered by overladen trucks, each painfully listing and axles askew. We passed through a handful of road blocks swarming with soldiers and Kalashnikovs, a casual reminder that the majority of Mali is very much at war. In the distance we noticed a camper-van and as we drew closer spotted a German number plate, the first European registered car we’d seen since Senegal. Pulling alongside, mid-overtake we looked across and a familiar face was sat behind the wheel. Christian, grinning from ear to ear and waving enthusiastically. We pulled over and caught up on the last couple of weeks. He’d bought the camper-van off a friend in Mauritania, where he’d left his bus, and was going to have a trip around Mali and then sell it. “For the same price as I bought it,” he reasoned. “Well, a little less, I had a small accident,” he chuckled, pointing at sizeable dent in the side. We bid farewell, for the third time on the trip.

Late afternoon, as the glaring sun gave way to dusk, still some 20 miles from Bamako we seemed to pass an imaginary line, and all hell broke loose on the roads. I had been cautiously expecting it having done this journey multiple times before. It would appear that upon passing through Senou, the highway code is tossed out the window and it’s every driver for himself. An elderly, battered Hilux clearly unhappy at the speed of the queuing traffic decided instead to overtake. Horn blaring and forcing all ongoing traffic off the road he drove on the wrong side until he’d passed the obstruction. Shortly afterward, a teenager on a moped threw a wheelie as he overtook us, his passenger clutching on with one hand and cheering in celebration with the other. With our nerves increasingly frayed and our eyes frantically scanning for unlit vehicles camouflaged in the deepening dusk a motorbike swerved across the front of us, his back wheel missing our bumper by millimetres.

Having finally reached Bamako intact we went for dinner at Appaloosa, an American diner themed restaurant with the Malian waiters dressed in cowboys hats, plaid and chaps and the eastern European barmaids dressed in all manner of revealing creations. The food was good and it was a relief to escape the roads for a couple of hours before heading to the airport. Later that night I dropped dad at the new Modibo Keita international terminal on the outskirts of the city (named after Mali’s first president), and then turned back towards Bamako, alone at the wheel for the first time in weeks.

The following day I spent a frustrating morning at the customs office dodging bribes and trying to ascertain the process of temporarily importing the truck, before giving up empty-handed and driving back down south to work. At the same time, Dad was transiting through Morocco, air travel warping the comparatively glacial relationship between time and distance that we had both inhabited.

Over the next two months, I settled back into my work routine (www.critcareint.com). After weeks of roaming the camp felt small and claustrophobic, Sundays offering the only chance to get out for a couple of hours and explore. One of the engineers gave me a tour of the construction site where the process plant was being built, soon to be eating up rock and spitting out gold. We also visited the beginnings of the open pits, merely scrapes in the ground at this early stage.

After a few hours marvelling at the powers of modern construction, and seeing what a hundred million dollars can build you, we visited some of the local artisanal mining areas. Mali has been mining and exporting gold since the thirteenth century and the local population still make a living from the earth. Shafts are dug by hand and can be over 50 metres deep, following the highest grade ore. Buckets of rock are pulled up to the surface, before being crushed and washed to release the gold dust, each tonne of earth giving up only a couple of grams of gold.

In between work, I tried to write these articles. What I had hoped would take six weeks — an article a week — in fact took many months. How naive of me. Only now, some six months later am I putting the finishing touches to the final piece. At times nothing readable flowed; the sights and sounds and smells awkward and uninspiring on paper. So instead, I read and tried to gain some inspiration from those who had been there before and done a masterly job, mainly Paul Theroux, his prose always evocative, addictive and lucent.

“I had learned what many others had discovered before me — that Africa, for all its perils, represented wilderness and possibility. Not only did I have the freedom to write in Africa, I had something new to write about.” — Paul Theroux

As the weeks progressed it became clear that temporarily importing the Land Cruiser wasn’t going to be as cheap or simple as I had initially thought. African bureaucracy and bribery stood in the way at every step, my question met with a different response every time, the price steadily increasing and always the risk that my application would be denied and the truck seized. I started to contemplate a return journey. The thought of heading back alone didn’t fill me with excitement, up until then I had planned to keep the truck in Mali and use it to explore west Africa when I wasn’t working. However, with the bureaucratic hurdles steadily mounting I decided it was my best option and with only a few weeks to go I began to put the necessary preparations in place. Security was by far the most pressing concern, my planned route northwest from Bamako and through the Mauritanian interior posed far more risk than the route we’d taken on the way down. I spoke with Christian who was reassuring having driven the route multiple times over the past decade, without incident. I spoke with others, did more research and eventually decided I was happy. Everyone has their own danger threshold and I was satisfied that the risk was sufficiently remote.

After seven weeks of work and with only a few days to go before my temporary import permit would expire, I loaded up with food and water, stocked the fridge with coke, topped up the radiator, checked the oil and set off for Bamako.

At 4am the following morning I left Bamako on empty streets and made my way to the Mauritanian border. The road was a cratered mass of potholes and crumbling concrete which slowed progress and ate into the day. I wanted to reach the border by early afternoon so that I could find somewhere to camp in Mauritania before dusk. Luckily, after a lethargic start the road split, one fork heading to Senegal and the other to Mauritania. At this point the tar finally became flat and road-like and I was able to make good time. I reached the border just after midday, pleased to be on schedule. However, the border guards, all twenty of them, were in the midst of an extended horizontal lunch break and told me the border opened again at 1700. There was nothing to do but sit and wait and hope that no one in this corner of the Sahel fancied taking a foreigner hostage. Getting bored, I decided I’d try and change some money and buy vehicle insurance for Mauritania. Both were easy enough to sort out and then I sat and chatted to Abdul Saboar, a Nigerian, gentleman, and his wife. He was en route to Mali to spend time studying the Koran and learning from the best, apparently the depth of Islamic education he desired wasn’t available in Nigeria. He was cheery and chatty and enquired about my own situation in his comical, high-pitched English, each syllable carefully considered as it squeaked out.

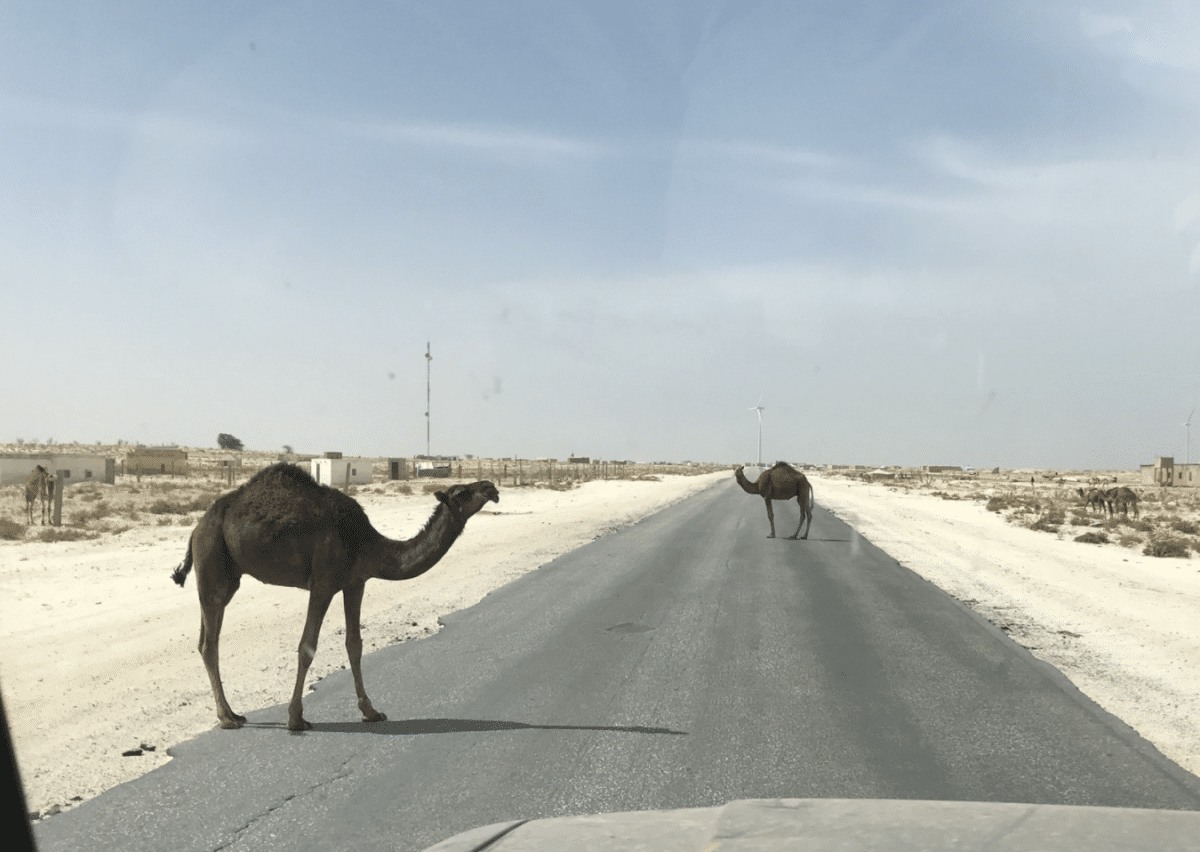

Nearly five hours after arriving, I was finally able to start the visa process, which involved speaking to about eight different people in eight different rooms, each inspecting my passport and documents and adding their signature and stamp. Finally, with only another hour of light left I was released into the empty wilds of Mauritania and sent on my way. The road was terrible and littered with donkeys, goats and camels; some alive and many dead. I sat hunched over the steering wheel staring into the blackness beyond hoping I’d see something loitering in the road in time to avoid it. The camels seemed to particularly enjoy strolling down the middle of the road.

My research had suggested it would be a 5-6 hour drive after the border to the nearest place to spend the night, in Kiffa. At 9pm, I was less than halfway there and running through the options in my head; what if it’s shut, will I be able to find it, shall I just drive through the night all the way to Nouakchott? With my eyes focused on avoiding livestock, I almost didn’t notice a compound appear on my left, an angular anomaly in the sand. I turned around and drove over for a better look. Across the archway was the magic word — ‘Auberge’. The relief was overwhelming.

The next morning, I woke early and looked at the map, I was on the outskirts of Ayoun El Atrous and it would be a 500-mile day ahead to Nouakchott. More than any other day of the drive, it is these 500 miles that will be forever imprinted on my psyche. I drove for over 12 hours through an apocalyptic, emaciated, sandy brown landscape. Death seemed to be achingly close; in places piles of dead and bloated goats and camels lay rotting in the sun. The only signs of life, the occasional flock of livestock accompanied by shepherd boys no more than ten, seemed painfully close to the edge. Dotted at random were family compounds of thick mud houses, sometimes hundreds of miles between them. Why live here I pondered, why not move? It seemed incomprehensible that anyone could eek a living from this baked, arid terrain. As the day groaned on it felt like the landscape was absorbing all my thoughts, I had to consciously decide what to think about and force a conversation in my head. At times I wondered if this was a stupid idea, travelling alone through somewhere so empty. No sooner had I agreed with myself that indeed it was and that next time I would be more careful I found myself overcome with a profound gratitude, realising how privileged I was to be driving through a country few have heard of, even if it was putrid and decaying.

As the afternoon edged away I stumbled upon the outskirts of Nouakchott, the roads growing increasingly crowded as I made my way towards a central hotel. The traffic trudged along, embodying an apt metaphor of African stagnation, bad government and short sightedness. If only each driver, each cog in the traffic, followed a common law of the road and substituted pure self-interest for the collective good. Maybe then each of us could slowly make progress, and I could get to my hotel and enjoy a cold coke and a hot shower. On the hooting, screeching and revving roads of Noakchott it made for an unpleasant and woefully slow commute, when extrapolated to nations it had crippled Africa and left citizens, like those I spent the day driving past, clinging to a baked and empty desert, trying to save themselves while their leaders jumped the queue.

The hotel was everything I dreamed, and more. At dinner, I ate alone and enjoyed overhearing a group of Russian men becoming increasingly exasperated as they tried ordering a round of beers, in a completely dry country. Getting into bed I felt I was violating the crisp white sheets with my dust and sweat-addled body, even after a long shower. A momentary thought before falling deeply into sleep.

Early the next morning I was back on the road — empty now at 4am — en route to Nouadhibou and the Moroccan border. Now that I was close to the coast, the blustering wind buffeted and pushed me around the road. In Nouadhibou, I caught a glimpse of the iconic iron ore train, which can be up to 3km long and runs 670 km inland. It’s clearly a lifeline for those living in the interior, I stood and watched as herds of goats were passed down from their perches on top of the ore-filled carriages, ready to be traded at one of the local markets. I recalled a fantastic piece in Sidetracked magazine (and since republished on Maptia), a group of surfers riding atop the train all the way from it’s beginnings at Zouérat to its terminus at Nouadhibou, where they hoped to catch the waves as they rolled down the coast (https://maptia.com/jodymacdonald/stories/journey-through-the-sahara).

I refuelled and picked up some supplies in Nouadhibou before continuing onto the Moroccan border, proceeding through each of the stations, about seven in all, my passport and vehicle registration document inspected and signed in turn. By the time it was over I was out of daylight and stopped at Hotel Barbas for a chicken tagine and an early bed.

The first hours on the road each morning were normally a pleasure, at 4am it was cool enough to drive with the windows up, the roads were clear and a calming sense of freedom would come over me. After a few hours, as the sun jumped above the horizon, this calm was burned away. I would stare ahead uninterrupted for hours, the black ribbon winding away interminably in front of me. At times like these, with a homogenous, sandy blanket horizon stretching into the distance and nothing to distract me, I dreamed of home, longing to be back in the U.K. As the day progressed past midday, each subsequent mile seemed to take longer and longer and I imagined how much better life would be when I was back home.

By mid-afternoon on day six — after a 500 mile marathon behind the wheel the day before — I was bored and tired and decided to pull over after only seven hours driving. At this point, the riskiest and most remote parts of the journey were behind me and I debated how to go about the rest of the drive. Take it slow and enjoy each country as I passed through, or power on and get home as soon as possible. Each afternoon I made a different decision. Motel Ribis, on Agadir’s southern edge, seemed to have been transplanted from an English seaside town with its big area of plastic tables and chairs next to the swimming pool, and the all day restaurant. A group of Moroccan teenagers, a double date, flirted and giggled amongst themselves as I sat alone reading and eating. Seafood gratin, seafood covered in melted cheese, a revelation and certainly the best meal of the trip so far.

A day of motorway driving followed out of Agadir, it was to be my last full day of driving in Morocco and I planned to stay half an hour south of Tangier. For hours the only distraction were miles of pink and mauve flowering bushes filling all the space between the carriageways. Later on, the motorway began passing by large infrastructure projects, a grandstand view of development on a seemingly huge scale. At one point twenty diggers, lined up end-to-end were excavating a trench ready for sections of piping to be laid. Next, a railway that looked like it had just been finished, immaculate and repetitive, workers carrying out the final touches before it carried it’s first passengers. I drove alongside for hours wondering how far it went and how much it must have cost.

Half an hour south of Tangier I set about looking for somewhere to stay. The roads became smaller, eventually turning to dirt as I searched for Dar Fkrum, a guesthouse looking out towards the distant Atlantic and surrounded by rolling fields of barley. A slightly shorter, dumpier Meryl Streep lookalike showed me to my room. It was the perfect place for a retreat I thought — no internet, a smidgen of phone signal and a wafting soundtrack of groaning donkeys — I decided there and then to stay for two nights. A day off was sorely needed after 7 days and 5000 km of driving.

The following morning, after a breakfast of homegrown strawberries and and a stilted chat in English-French-Spanish, I settled on the sofa to read. In the afternoon, I strolled through barley fields, the grasshoppers dancing about my feet, down to the beach and back before another excellent meal and evening chat with Clara.

The next morning, I sailed out of Africa. Once on European soil I began following the back roads through Spain and discovered a different country to the one I had driven through months ago. I remembered a flat, bleached, tired palette and to my surprise found very much the opposite.

France passed by in a crumbly haze of puff pastry, baguettes and cheese. With no deadline I slowed down a little, sampling as many patisseries as my gut would allow and making sure to be camped up by mid-afternoon so I could enjoy a quiet evening with a book and dinner.

After twelve days on the road I boarded the Euro Tunnel to cross the final border of the trip. Mali felt a world away as the train rumbled under the channel. I negotiated the frenetic M25, dawdling along in the inside lane as every other vehicle took their turn overtaking. The last few miles ticked away and then I was home. Back on the crunchy gravel drive I had crawled off over 3 months ago. I embraced my mum, unpacked a couple of things and sat down for a cup of tea and cake. I had successfully commuted to work and back. I had explored west Africa overland, seen places untouched by tourism and technology and now I was home safely. It was overwhelming.

In the months after returning home, I reflected on what had made it such a fulfilling journey. Each of us, I believe, has a mental model of the world, a neurological canvas onto which we project ourselves and our experiences. Any chance you get to develop and refine your model you should take. For most people, the distance between fact and their mental fiction is cavernous. Bigotry, racism and war often stem from this cerebral deficit, a disconnect between the real and the imagined. Travel serves to align the two, bringing ones imagined world more in line with the lives for whom it is reality. I figured that once the views, sunset beers and dusty roads had faded, my understanding and appreciation of the cultures we had passed, my insight into their lives, would burn on. For this opportunity, I was immensely lucky.